24 Jan A behavioural problem, you say? There’s a bias for that!

What is the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the words “behavioural design”?

System 1 and System 2?

Daniel Kahneman?

Cognitive biases?

The latter is often seen as the foundation of behavioural design.

When we established /KL.7, very few people knew what behavioural design was. Today, many people in most businesses can name at least five cognitive biases.

However, cognitive biases do not explain behaviour. They describe behaviour.

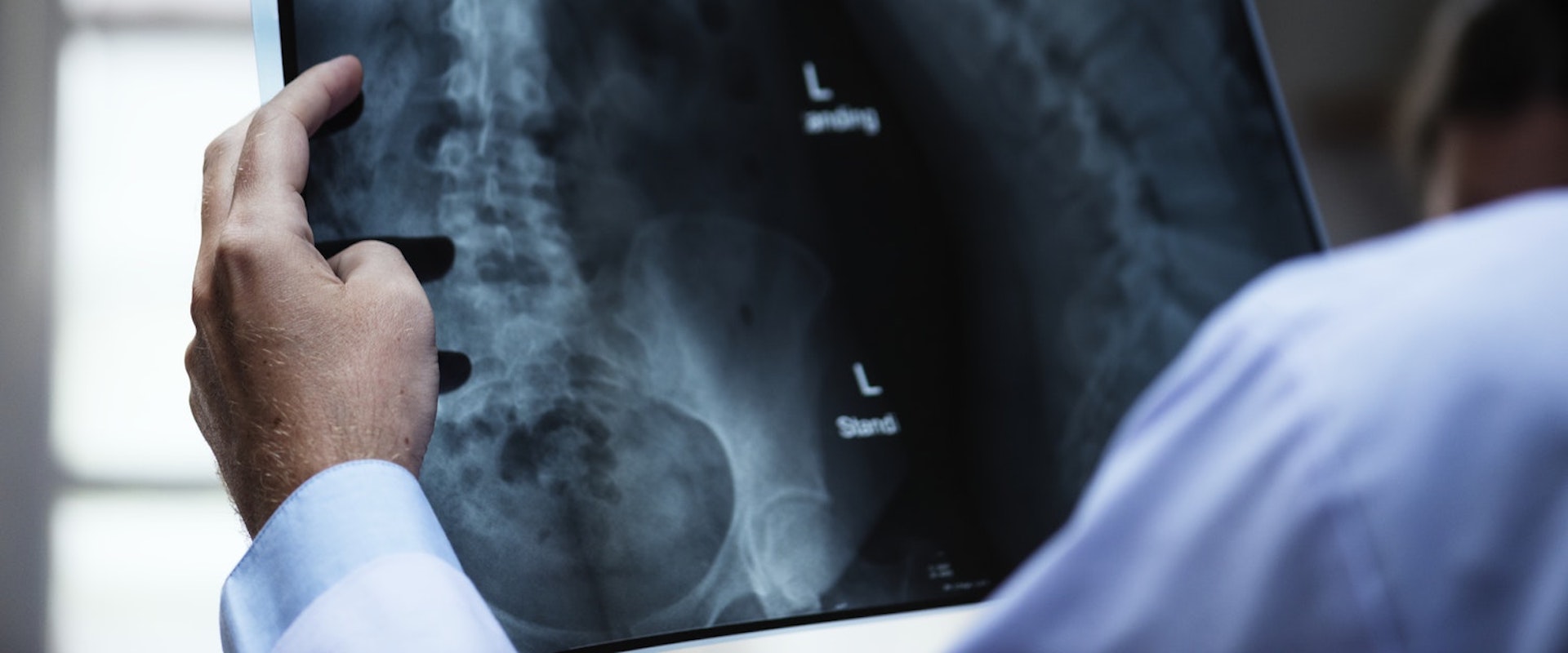

Similar to how a good clinical treatment or an operation requires a solid diagnosis, the solutions to your behavioural problem is completely dependent on properly understanding the problem first.

So allow me to acknowledge the diagnosis for its importance – and let me explain how to properly execute the diagnosis of a behavioural problem.

There a bias for that

The light translation of “There’s an app for that” in the title of this article summarises well how it is being a behavioural designer in 2019.

The field has been infected by biases. Or as Fabrizio Ghisellini, co-author of Behavioral Economics – Moving Forward, says:

“…we have a discipline plagued with confusing definitions, unanswered questions and conceptual gaps—a new bias every day.”

We celebrate that the field has achieved such broad fame – we have popular tv-shows, podcasts, and much more covering the subject.

However, holding a scalpel in your hand doesn’t make you a good surgeon.

When aesthetics take over

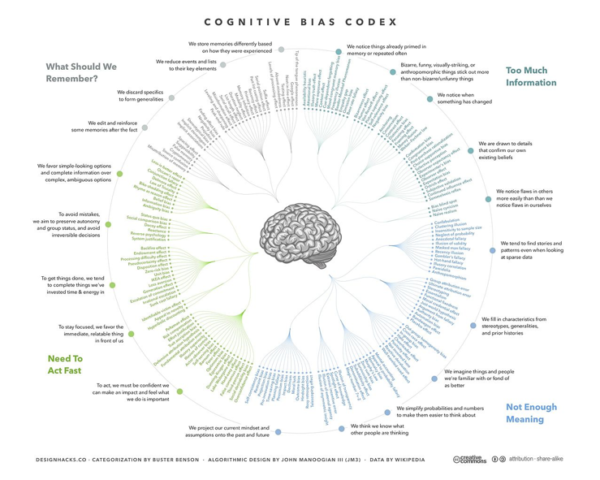

The list of biases on Wikipedia is now at 191 and counting. So what to pick?

More and more attempts to solve complex behavioural issues seem more like a bunch of blindfolded monkeys throwing darts at a list of biases.

Is you simply throw enough darts, you’ll probably hit the bull’s eye at some point (in other words: it is a remarkably inefficient and expensive approach).

Other attempts to communicate behavioural design in a simple way has lead to more aesthetic strokes of “genius”, such as this:

Undeniably an impressive piece of work – visually. However, as you may have noticed, many of these biases are opposing each other.

For instance, optimism bias (look at the illustration as a clock, and it is located 7 o’clock) and negativity bias (11 o’clock).

What to pick, then?

Bias overload

Ironically, both the list and its beautiful presentation is a great example of information overload – a phenomenon leaving the designer paralysed with no other option than retaining status quo – “I’ll go with what I’m used to. But now I’ll call it behavioural design”.

This type of communication is both neutral, because the design is ineffective, but also ruins the seriousness of the field.

Had the case been the same when clinical surgery was introduced in the 1900’s, the discipline would have never left the barbershop (the barber already had the tools; why even categorise it as medical practice?).

As demonstrated in our series on Nudgebusters here and here, you cannot simply throw darts at a list of biases and hope to achieve great results – pretending that it has anything to do with behavioural design.

This is how you diagnose

Follow these three tips on where you can properly apply your x-ray in order to facilitate a diagnosis more profound than regular surveys.

Naturally, they do not provide a complete overview, but they’re a good place to start.

1. Make time for your diagnosis

It seems simple, but it is the first step towards designing better solutions. Any process within behavioural design should spend at least 1/4 of the ressources on the diagnosis (unless the context has been diagnosed previously). It simply increases the probability that you solve the right problem – from random chance to highly likely. When is the last time you spent 25% of the ressources to diagnose in a project?

2. Map out structural barriers

Barriers that provoke the wrong, psychological tendencies in the target group. For instance, lack of a deadline is a basic issue in getting Danes to switch banks. The willingness appears when life events introduce a deadline – e.g., purchasing a house – even though they can switch banks both cheaper and better at any time.

3. Identify subtle motivational structures

For instance, the amount of parking spaces reserved for an organisational department may produce leaders that focus more on hiring new employees than creating cost-effective teams. Simply to signal the status they have chased their whole life.

And remember that it is hard to find anything more complex that human behaviour in the real world.

A problem can have many causes

Only rarely does a behavioural problem have one single cause. There can be many different explanations of differing importance. And there will be contrasting explanations throughout the project.

The behavioural designer’s most prominent job is to find as many causes as possible – and only then find the tools most appropriate.

Maybe one bias. Maybe two.

Maybe none.

Fortunately, the barber is no longer the surgeon – the stringent evidence of natural science is beginning to trumpf comfort.

At /KL.7 we don’t doubt that behavioural design will look like natural science more and more – even though our post-factual society may pose a small bump on the way. The question is how fast we’ll get there – and with whom.

Personally, I’m glad that surgeons take their time in their diagnosis, before cutting us up.