24 Oct This is how you design for human beings (A key to Google’s success)

Google is often mentioned as a prime example of what you can achieve by using data for insights. In reality, however, much of Google’s success relies on the on application of behavioural science. Particularly, Google’s way of reducing the complexity of the Internet to one simple interaction.

For instance, just below the search bar, Google tells you the time spent finding the results for your search query. How come?

This little piece of information is a kind of sugarcoated valium to our inner monkey (or System 1). Why? It gives clear and quick feedback that the expense of searching is extremely little.

At this point, even a monkey will know that another search won’t be much hassle.

In fact, speed is such an important factor that fast search results have shown to be three times as important as better search results for users.

On top of that, Google guesses what you actually meant, when you type in half-finished sentences.

However, users wouldn’t have recognised or acknowledged this fact in a qualitative interview. Our basic abilities – also know as the monkey – simply do not have a language.

Fast rather than perfect

When Google asked what the users wanted, they replied “Perfect search results”. However, the users’ behaviour showed that the preferences had little to do with quality.

Likewise, it is rarely the answer to produce more brochures when the user ask for more information in your focus-group on dietary habits, digital safety or climate adjustments. There is a tacit answer for everything that we find difficult to respond to – and this answer rarely covers what is actually needed to change behaviour.

Allow me to take a step back in history.

Where lies the origin of ‘behavioural design’?

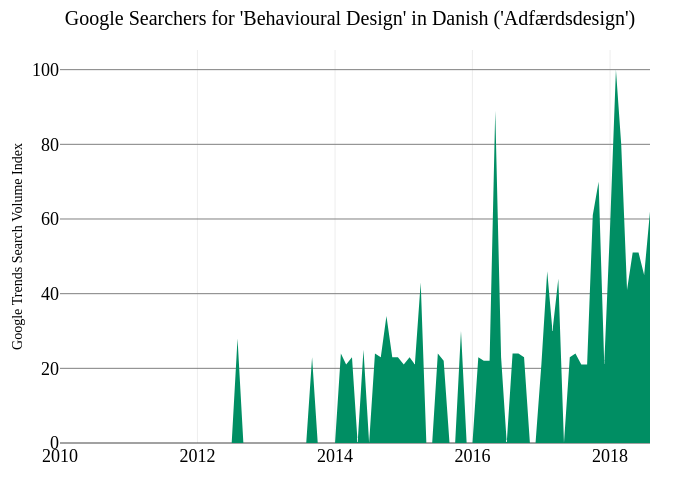

Back in 2011, when we first started /KL.7, no one were familiar with the term behavioural design (in Danish “Adfærdsdesign”). It didn’t exist.

Instead, people spoke about nudging and to us that term does not imply good a behavioural design.

In the beginning, we weren’t concerned with the fact that there was no term for the discipline. In august 2012, however, we officially decided to name it ‘Adfærdsdesign’. From there on – at least according to Google – the word continuously spread (in this relation, the Danish Ministry of Culture deserves great applause for being the first public institution using the word back in 2013):

Throughout the process, we considered more insight-oriented terms (inspired by the Behavioural Insights Team) and engineer-sounding names for our approach. The latter was inspired by the technique and precision within the discipline.

Anyway, we ended up with behavioural DESIGN.

Because that’s what it is.

Behavioural design is about designing an object, a product, an interface, a system, a procedure, a program, communication and so forth – all with the ambition to change people’s behaviour for the better.

In this regard, design is about specific, structured processes with the aim to better the user’s life – not necessarily aesthetics.

Logical or biological design?

Behavioural science introduces a very central element – that humans are far from rational individuals with consistent opinions and preferences.

If we consider our abilities, we are born with solid skills and preferences developed through millions of years – these are basic abilities. Among those, we find basic mathematics, our spatial awareness, and the urge to make defensive decisions.

In the end, we’re all just humans

The basic abilities are not to be confused with our taught abilities (the ability to read, for instance) or the ability to reflect philosophically on human existence. We share our basic abilities with other species and they are found independent of culture. From the child in a rural city in Thailand to the retired business man in New York.

This is why a product rarely will turn out to be a success, if you design against the user’s basic abilities – while designing for them give you a much greater chance for success.

Basic abilities are always present in any human being across the globe, while many taught and intellectual abilities vanish as soon as we lack sleep, food, or are stressed out.

It is also, typically, in this state, that marital disagreements occur – given that our basic abilities are focused on an ego-centric view of the world (“Why don’t you understand, you have exactly the same information as I do!?”).

Basic abilities always provide the best starting point

In other words, it is ALWAYS a good idea to design for the most fundamental aspects of humans, simply because you can never know the current cognitive state or situation of your user, in any given moment.

“Biological design” means designing for everything that is inherently passed on in our biology. On a side note, that’s how you make intuitive products (like when a 2-year old knows how to use an iPod, without any instruction).

Designing for basic abilities aren’t always enough to guarantee success, but it’s a necessary starting point. It is much(!) easier to design natural products than the attempt to change human nature (the latter easily takes a few generations).

How you design for real humans

The most essential value creation of behavioural design is the application of more than 80 years of research, exploring how humans actually behave.

This approach lies far from seeking to understand your target group as if they were a new species that had just arrived on Earth. Or thinking that characterising them as ‘women looking for a place to live’, means that they are no longer bodily aware, will easier recognise things in great contrast, or will avoid activating mental resources at great expense.

In short, we already know a lot about human beings; what they can and cannot do, what their needs are, when or how they wish to apply tools – and that’s even BEFORE we receive the brief on any given project.

Behavioural design is a reasonable stubbornness to apply all the knowledge that we already have on Homo Sapiens, rather than constantly wanting to start over, for each target group. The target group always consists of human beings (unless you have a really interesting business model).

Mikkel er en af landets førende rådgivere om den datadrevne organisation. Med en PhD i IT-design og som medforfatter på bogen Data - Virksomhedens nye grundstof er han en flittigt brugt oplægsholder og rådgiver for store og små, offentlige og private virksomheder. Mikkel sidder endvidere i regeringens ekspertgruppe for dataetik.