12 Oct Nudge Busters #1: (Anti)social norms?

Nudging and behavioural design is popular like never before. However, this popularity can lead to some unfortunate attempts of applying behavioural insights as if they were fairy dust that magically change human behaviour.

Trust me, they’re not.

Best case scenario, these sorts of quick-fix nudges only lead to a waste of time and money. Worst case, one can end up with implementing interventions that have the opposite effect of what was initially intended.

This is the first article in a series of ‘nudge busters’, where we will take an extra look at some ‘nudges’ and attempts of behavioural design that have been executed poorly. Along the way, we will explain what went wrong.

We’ll begin with a well-known principle within behavioural science – social norms.

Human beings are herd animals

We human beings are social animals and it is important for us to belong to a group. It is evident in the way we try to mirror the behaviour of others in the group.

When we have a shared, common behaviour within a group, it’s called a social norm.

In short, a social norm describes a behaviour that is characteristic of a group.

So, when different webshops show the text “9 out of 10 visitors have also bought <product name>” or “people who have bought <product name X> also bought <product name Y>” this is it a fully conscious decision: The webshop is trying to nudge you into buying a product by showing you what others have done.

The principle of social norms work, but that doesn’t mean that it’s the most efficient behavioural insight to use in your domain.

Scientists can also be mistaken

People not showing up for their scheduled doctor’s appointment is very expensive for hospitals.

In 2015, a group of British scientists wanted to investigate if SMS-reminders can be used to lower the number of people who do not show up at their scheduled doctor’s appointment.

Text messaging is a cheap way of communicating with people. It’s also easy to experiment with the content and find out what provides the best solution.

The scientists tested four different text messages, some of which included behavioural insights principles as shown below.

| Message | Wording |

|---|---|

| Control | Appt at [clinic] on[date] at [time]. To cancel or rearrange call the number on your appointment letter. |

| Easy Call | Appt at [clinic] on [date] at [time]. To cancel or rearrange call 02077673200. |

| Social Norms | We are expecting you at [clinic] on [date] at [time]. 9 out of 10 people attend. Call 02077673200 if you need to cancel or rearrange. |

| Specific Costs | We are expecting you at [clinic] on [date] at [time]. Not attending costs the NHS £160 approx. Call 02077673200 if you need to cancel or rearrange. |

The first text (Control) is a control-text without any form of nudging attempts.

The second text (Easy Call) contains the phone number that you are supposed to call in need of a cancellation. Within behavioural science, it is a well known principle that simply making a behaviour or action easier increases the likelihood that people do it.

The third text (Social Norms) also contains a “social norm”: 9 out of 10 people show up for their doctor’s appointment.

The fourth text explains to the receiver how much it costs the British health care system if you don’t show up or don’t cancel your doctor’s appointment. Simple, rational information; the opposite of nudging.

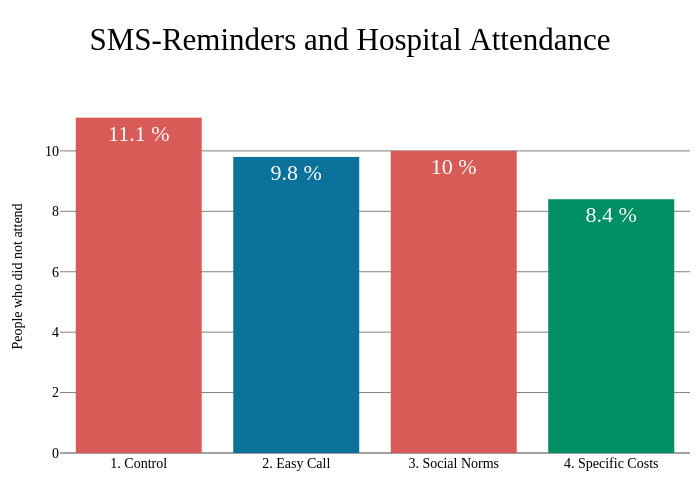

The text messages were sent out to thousands of Brits and the results of the experiment look like this:

The fourth text was the most effective.

At a first glance, the effects look quite small, but if the British health care system send out messages using the fourth text, it would lead to approximately 5.800 fewer missed appointments. Not a bad return on investment for sending out a simple SMS-reminder.

“But what about the power of social norms?!”

“9 out of 10” doesn’t prescribe any sense of belonging to the receiver. A social norm only works if the 9 out of 10 people belong to a group that I as a receiver of the message identifies with.

I don’t know about you, but I don’t feel any sense of belonging to a group of people I don’t know anything about – the rest of the people who have booked a doctor’s appointment?

On the other hand, I can easily understand the causality between the increased over-all costs for the British health care system and my missing cancellation.

Social norms work, yes, but that doesn’t mean they are the most effective behavioural insight to leverage. Especially in domains where defining an identifiable in-group is difficult.

A much bigger issue with the experiment

Besides a shallow understanding of how social norms work, there’s a much bigger problem with this experiment.

Go back up to the table with the four text messages and see if you can figure out what the problem is.

The researchers mixed together different sorts of nudges in the same texts.

Text number four states both the cost of a missing cancellation and the phone number for cancellations.

So really, we cannot conclude which of the two nudges in the text messages that had the biggest effect on the receivers.

Behavioural design and nudging are very effective tools. But knowing a list of cognitive biases and other behavioural insights doesn’t lead to efficient interventions and designs. Methodological precision and expertise, on the other hand, does.

Do you know of any nudges or experiments in behavioural design, that you find hard to believe or that you want us to throw under the microscope?

Feel free to send them to us, at nudgebusters@kl7.dk.

Kristian is /KL.7's language expert – he has the responsibility for the linguistic and conceptual parts of both analysis and reports, as well as methodological design and intervention design. Kristian has experience working as a scientific journalist with the Danish newspaper, Jyllands-Posten, and has previously been part of the Apprentice program of the agency, Red Associates, working as a strategic consultant. Kristian is skilled on both a level of great detail and in bigger decision making processes.