12 Dec How to avoid the 3 most common mistakes in surveys

As users, we’re getting bombarded with surveys – be it user research or customer satisfaction programmes.

I may receive at least one questionnaire a day, in my personal mailbox.

- What did you have for dinner a week ago?

- How often do you visit the theatre?

- How many times did you air out your apartment last week?

It is obvious, of course, that most of us find these surveys extremely annoying – most of us end up responding to only a few of them, if any at all.

But really, traditional surveys and questionnaires pose one primary issue: They tell us very little about your user’s, customer’s, or employees’ actual behaviour.

Disagree?

Here’s a few curious facts:

- More than 80% of all French men believe they’re better lovers than the average guy

- More than 70% of all Swedish drivers believe they’re better than the average driver

And if you think that this inability to answer truthfully only applies to others, try and answer the first question asked in this article: What did you have for dinner a week ago?

Most people have difficulties remembering an everyday event like this. Unless something extraordinary happened – or you have a super memory.

If I’m not mistaken, you probably even spent a few seconds figuring out what day it is today. In that case: Don’t worry, you’re perfectly normal.

The important discrepancy between self-report and actual behaviour

When we can barely remember what happened a week ago, how are we supposed to answer how many times we use public transportation the last month? The last time we bought washing powder? The last time we visited the theatre?

We may be able to give a proper estimate if we really spend time looking at the calendar, our bank account, or our receipts. But no one does that in a busy everyday life.

Nobody. We’ll give our best guess. And often it’ll be far from the truth.

Or as VP of R&D Innovation Julie Setser at Procter & Gamble stated:

“The traditional large survey-based research is too expensive, too slow and over a hundred years old—it’s an ancient obsolete approach. But most importantly, it’s just not predictive. Asking consumers what they want, what they need, what they’re going to do in the future, is just not predictive of what they actually will do.”

This is evident both nationally and internationally, where 70-year old experiments have shown that people don’t even know whether they own a library card.

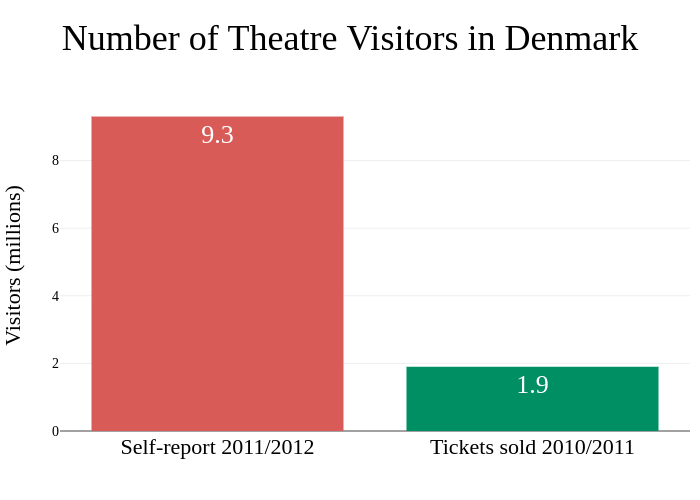

Another example is the Danish national survey on cultural habits from 2012, that showed that Danes visited the theatre four times more than the number of tickets sold.

Most commonly, behavioural data (observing behaviour rather than asking about it) is favorable when answering such questions.

Behavioural data is available to most companies in some sort; e.g. customer data bases, purchase statistics, measuring equipment, Google Analytics and so forth. However, far from everyone uses them strategically in order to generate insights into the actual behaviour of their users or customers.

When ‘the suit’ takes over

You may have already heard of Daniel Kahneman’s explanation of the two ways of thinking; System 1 and System 2. In /KL.7 we have personified the two systems, calling them the ‘the monkey’ and ‘the suit’.

The monkey, our System 1, is automatic, incredibly fast, intuitive and inaccessible to our conscious self. The suit, our System 2, on the other hand, is slow and rational. We believe we’re the suit, rationally thinking. However, in reality, we’re controlled by the monkey in the majority of our decisions and behaviours.

What does this mean for the design of your survey?

When we seek to understand why citizens, customers, or patients do what they do, what we’ve just established is imperative. While the suit can find explanations for our behaviour, there are many pieces and bits of information hidden away in the monkey’s behavioural patterns. And these pieces of information may be essential for understanding actual behaviour.

Seeing that the monkey controls our behaviour and decisions, it is essential to apply methods that consider why the monkey acts as it does.

This is a crucial point. It is crucial because it should influence how we design surveys and analyse data. When we simply trust everything the suit says – without conferring with the monkey – we’ll miss out on key insights on human behaviour, mental models and motivation. Key insights on how we find solutions to behavioural problems.

Avoid the 3 most common mistakes in surveys

The great news is that you can avoid these mistakes fairly easily if you’re familiar with them. And in a minute, you will be.

Mistake number 1: Never expect correct answers in self-evaluations – the respondents will overestimate themselves and underestimate others. The case with the French men overrating their intimate abilities isn’t unique: We systematically overrate ourselves while underestimating others. Often, we’ll get to know more about the norms in a specific behaviour by asking for an evaluation of others – for instance friends or acquaintances.

Mistake number 2: Never expect correct answers to questions about one’s own behaviour – respondents don’t have a perfect memory. A lot of guessing is involved when we’re answering questions on our own behaviour. In general, surveys can tell us about intentions, experience and attitudes. If we seek to know about actual behaviour, we have a long way to go from there.

Mistake number 3: Never expect correct answers to questions on explanations for a specific behaviour – the respondents can only access one part of their decision making processes. The suit. The suit will rationalise decisions made by the monkey in hindsight. This is why we’ll end up with invalid data on why people behave as they do.

What then? Should we get rid of surveys completely?

Most certainly not. But we must be aware of the things that we can actually respond to, and where we must use other methods to understand why people behave as they do.

In /KL.7 we have developed a set of methods that are combined with behavioural science, allowing us to map out and understand the monkey’s decisions – including the motivations that lie behind them. This set of methods also contains ways of using surveys that come closer to uncovering insights about actual behaviour.

We call this behavioural analyses.

Are you or your organisation challenged with obtaining a deeper understanding for how you may achieve behaviour changes in your target group?

In that case, feel free to contact me and hear more about how behavioural analyses can provide actionable insights for your organisation.

Lilie has a master's degree in the Science of Public Health, specializing in methodological design, among other things. She has great experience with creating valid research designs along with the analysis and synthesis of both qualitative and quantitative data.